Key Takeaways

- Common myths about creatine, such as it causing kidney damage, weight gain, and being a steroid, are widespread but unsupported by scientific evidence.

- Each myth will be debunked with research-based information, providing clarity on creatine’s true effects.

- Creatine offers several benefits, including enhanced muscle strength, improved exercise performance, and cognitive advantages.

- Safe and effective usage guidelines will be provided to maximize benefits and minimize potential side effects.

Introduction

Creatine is a widely popular supplement in the fitness and bodybuilding communities, known for its ability to enhance muscle strength and performance.

Despite its benefits, creatine is often surrounded by myths and misconceptions that can deter individuals from using it or cause unnecessary concern.

Addressing these myths is can help individuals make informed decisions based on scientific evidence rather than misinformation.

Myth 1: Creatine Causes Kidney Damage

One of the most persistent myths about creatine is that it causes kidney damage. This belief stems from the misunderstanding that creatine supplementation puts excessive strain on the kidneys, leading to potential harm.

Numerous studies have shown that creatine supplementation does not cause kidney damage in healthy individuals. Research involving both short-term and long-term creatine use has consistently found no adverse effects on kidney function.

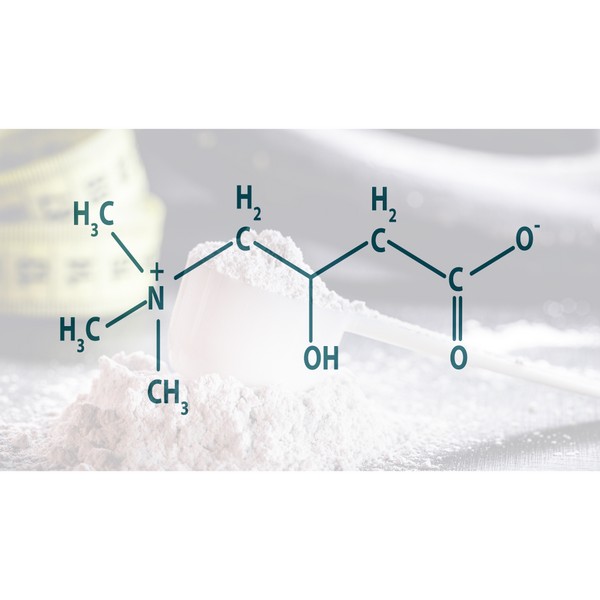

Creatine is naturally produced in the body and stored in muscles as creatine phosphate. When supplemented, creatine is absorbed in the intestines, enters the bloodstream, and is taken up by muscle cells.

The kidneys filter creatinine, a byproduct of creatine metabolism, which is then excreted in urine. This process is a normal function of the kidneys and does not indicate damage or stress.

Myth 2: Creatine Leads to Weight Gain and Bloating

A common belief is that creatine supplementation leads to significant weight gain and bloating, deterring some individuals from using it.

Differentiation Between Water Retention and Actual Weight Gain

Creatine can cause an initial increase in water retention within muscle cells, which may result in a slight weight gain.

However, this is not the same as gaining fat. The increase in water content helps the muscles perform better and recover faster.

Studies Showing the Effects of Creatine on Body Composition

Research has shown that while creatine may cause a temporary increase in water weight, it does not lead to an increase in fat mass.

Studies indicate that creatine supplementation is associated with increased lean muscle mass and improved body composition over time.

Myth 3: Creatine Is Only for Bodybuilders

Many believe that creatine is a supplement exclusively for bodybuilders aiming to increase muscle mass and strength.

Benefits of Creatine for Various Types of Athletes and Non-Athletes

Creatine offers benefits beyond bodybuilding. Athletes in sports requiring short bursts of energy, such as sprinting, swimming, and high-intensity interval training, can benefit from creatine.

Additionally, non-athletes, including older adults and those looking to enhance cognitive function, can find creatine useful.

Studies have shown that creatine supplementation can improve cognitive performance, particularly in tasks requiring short-term memory and quick thinking.

Furthermore, creatine has been linked to overall health benefits, such as improved muscle function in older adults and neuroprotective effects.

Myth 4: Creatine Is a Steroid

A widespread myth is that creatine is a steroid, leading to misconceptions about its safety and legality.

Explanation of What Creatine Is and How It Differs from Steroids

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound found in small amounts in certain foods and synthesized by the body. It serves as an energy reserve in muscle cells, enhancing the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during high-intensity exercise.

Steroids, on the other hand, are synthetic substances that mimic hormones like testosterone and have a wide range of effects on the body, including significant hormonal changes.

Clarification of Creatine as a Naturally Occurring Substance in the Body

Creatine is endogenously produced by the liver, kidneys, and pancreas. It is not a hormone and does not influence the body’s hormonal balance.

Its role is to support energy production in cells, making it fundamentally different from anabolic steroids.

Myth 5: Creatine Causes Muscle Cramps and Dehydration

It is often believed that creatine supplementation leads to muscle cramps and dehydration, making it a concern for athletes and fitness enthusiasts.

Creatine and Dehydration or Cramps

Studies have consistently shown that creatine does not cause muscle cramps or dehydration. Research involving athletes who supplement with creatine has found no increase in muscle cramping or dehydration compared to those who do not use creatine.

Research suggests that creatine may help maintain electrolyte balance and reduce the risk of dehydration during intense exercise.

Hydration While Using Creatine

To ensure optimal hydration while using creatine, individuals should:

- Drink adequate amounts of water daily, generally recommended at 3-4 liters for active individuals.

- Monitor urine color as a simple indicator of hydration status, aiming for a light yellow color.

- Consume additional fluids during and after exercise to replace lost sweat.

Myth 6: You Need to Cycle On and Off Creatine

A common belief is that creatine must be cycled on and off to maintain its effectiveness and prevent potential side effects.

Why Cycling Is Unnecessary

Research indicates that continuous creatine supplementation is both safe and effective. There is no evidence to suggest that cycling creatine provides any additional benefits.

Long-term studies have demonstrated that sustained creatine use does not diminish its effectiveness or lead to adverse health effects.

Safe and Effective Usage Guidelines

For safe and effective use of creatine:

- Begin with a loading phase of 20 grams per day, divided into four doses, for 5-7 days to saturate muscle stores.

- Follow with a maintenance dose of 3-5 grams per day.

- Ensure consistent daily intake, including on rest days, to maintain elevated muscle creatine levels.

Benefits of Creatine Backed by Research

#TLDR Dr. Candow left you a summary. Buy creatine. https://t.co/KBFrwlOPAg

— D. Martin MS, CSCS, CISSN 🇺🇸 (@dmartinfitness) August 3, 2019

Enhanced Muscle Strength and Power

Creatine increases phosphocreatine stores in muscles, allowing for improved ATP production during high-intensity activities, leading to greater muscle strength and power.

Improved Exercise Performance and Endurance

Studies show that creatine enhances performance in high-intensity, short-duration activities like weightlifting, sprinting, and interval training. It also aids in quicker recovery between sets and workouts.

Cognitive Benefits and Neuroprotective Effects

Research indicates that creatine supplementation can improve cognitive function, particularly in tasks requiring short-term memory and quick thinking.

It also shows promise in neuroprotection, potentially benefiting conditions like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

Support for Overall Health and Well-Being

Beyond athletic performance, creatine has been linked to overall health benefits, including improved muscle function in older adults, reduced fatigue, and better brain health. Its role in maintaining cellular energy balance contributes to general well-being.

Safe Usage Guidelines for Creatine

Recommended Dosages and Loading Phases

- Loading Phase: For rapid saturation of muscle creatine stores, take 20 grams of creatine daily, divided into four 5-gram doses, for 5-7 days.

- Maintenance Phase: After the loading phase, a daily dose of 3-5 grams is sufficient to maintain elevated creatine levels in muscles.

- Alternative Approach: Skip the loading phase and take 3-5 grams daily from the start, though it may take longer to reach full saturation.

Types of Creatine Supplements Available

- Creatine Monohydrate: The most researched and widely used form, known for its effectiveness and affordability.

- Creatine Ethyl Ester: Claims of better absorption, though research does not show significant advantages over monohydrate.

- Creatine Hydrochloride: Known for higher solubility and potentially less digestive discomfort.

- Buffered Creatine: Designed to reduce the conversion to creatinine, though benefits over monohydrate are not well-proven.

- Liquid Creatine: Often marketed for convenience, but stability and effectiveness may be compromised.

- Creatine Nitrate: Combines creatine with nitrate for potential enhanced vasodilation and performance benefits.

Tips for Maximizing Benefits and Minimizing Side Effects

- Stay Hydrated: Drink plenty of water daily to avoid dehydration and support creatine’s effectiveness.

- Consistency: Take creatine daily, even on rest days, to maintain muscle saturation.

- Monitor Dosage: Stick to recommended dosages to avoid potential side effects like gastrointestinal discomfort.

Conclusion

Creatine is a well-researched supplement offering numerous benefits, including enhanced muscle strength, improved exercise performance, and cognitive advantages. Myths surrounding creatine, such as it causing kidney damage or requiring cycling, have been debunked by scientific evidence.

Base your decisions on robust research rather than misconceptions and anecdotal reports.

Creatine is safe for long-term use, beneficial for various athletes and non-athletes, and offers significant health and performance improvements when used correctly.

FAQs

Is Creatine Safe for Long-Term Use?

Long-term studies have shown that creatine is safe for extended use in healthy individuals. Research over several years has found no adverse effects on kidney or liver function.

Can Women Take Creatine?

Yes, women can take creatine and benefit from its effects. Creatine can enhance muscle strength, improve exercise performance, and support cognitive function in women, just as it does in men.

Does Creatine Affect Cardiovascular Health?

Studies indicate that creatine does not negatively impact cardiovascular health. Some research suggests it may even have beneficial effects, such as improving endothelial function and reducing homocysteine levels, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

What Is the Best Time to Take Creatine?

Research suggests that creatine can be effectively taken at any time of day. However, taking it post-workout with a carbohydrate-rich meal may enhance muscle uptake and recovery.

Are There Any Natural Food Sources of Creatine?

Yes, creatine is found in foods such as red meat, poultry, and fish. For example, beef and salmon are rich in creatine, providing about 1-2 grams per pound. These foods can help maintain natural creatine levels in the body.

Research

Antonio, J., Candow, D.G., Forbes, S.C. et al. Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 18, 13 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w

BURKE, D. G., S. SILVER, L. E. HOLT, T. SMITH-PALMER, C. J.CULLIGAN, and P. D. CHILIBECK. The effect of continuous low dose creatine supplementation on force, power, and total work. Int. J. Sports Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 10:235–244, 2000.

Bemben MG, et al. The effects of supplementation with creatine and protein on muscle strength following a traditional resistance training program in middle-aged and older men. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(2):155-159.

Branch JD. Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003;13(2):198-226.

Buford TW, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2007;4:6.

Candow, D.G., Chilibeck, P.D. & Forbes, S.C. Creatine supplementation and aging musculoskeletal health. Endocrine 45, 354–361 (2014).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-013-0070-4

Candow DG, et al. Effect of different creatine supplementation protocols on muscle strength and power in healthy young adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(1):232-239.

Candow, D. G., Forbes, S. C., Chilibeck, P. D., Cornish, S. M., Antonio, J., & Kreider, R. B. (2019). Effectiveness of Creatine Supplementation on Aging Muscle and Bone: Focus on Falls Prevention and Inflammation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(4), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8040488

Chilibeck, P. D., Kaviani, M., Candow, D. G., & Zello, G. A. (2017). Effect of creatine supplementation during resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 8, 213–226. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S123529

Chilibeck PD, et al. Effect of creatine ingestion after exercise on muscle thickness in males and females. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(10):1781-1788.

Cooper R, et al. Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2012;9(1):33.

Cribb PJ, Hayes A. Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(11):1918-1925.

Dalbo VJ, et al. The effects of polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on anaerobic performance measures and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(3):818-826.

de Souza E Silva A, Pertille A, Reis Barbosa CG, Aparecida de Oliveira Silva J, de Jesus DV, Ribeiro AGSV, Baganha RJ, de Oliveira JJ. Effects of Creatine Supplementation on Renal Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Ren Nutr. 2019 Nov;29(6):480-489. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2019.05.004. Epub 2019 Jul 30. PMID: 31375416.

Earnest CP, et al. The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995;153(2):207-209.

Gualano B, et al. Creatine supplementation and resistance training in vulnerable older women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:7-15.

Kreider RB, et al. Effects of creatine supplementation on body composition, strength, and sprint performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(1):73-82.

Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z

Kreider RB. Effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;244(1-2):89-94.

Mesa JL, et al. Oral creatine supplementation and skeletal muscle metabolism in physical exercise. Sports Med. 2002;32(14):903-944.

McMorris T, et al. Creatine supplementation and cognitive performance in elderly individuals. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2007;14(5):517-528.

Persky AM, Brazeau GA. Clinical pharmacology of the dietary supplement creatine monohydrate. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(2):161-176.

Rawson ES, et al. Effects of creatine supplementation and resistance training on muscle strength and weightlifting performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(4):822-831. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14636102/

Rae C, et al. Oral creatine monohydrate supplementation improves brain performance: a double–blind, placebo-controlled, cross–over trial. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270(1529):2147–2150.

Rosca P, et al. Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Exp Gerontol. 2019;124:110625.

Stout JR, et al. Effects of twenty-eight days of beta-alanine and creatine monohydrate supplementation on the physical working capacity at neuromuscular fatigue threshold. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(4):928-931.

Syrotuik DG, Bell GJ. Acute creatine monohydrate supplementation: a descriptive physiological profile of responders vs. nonresponders. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(3):610-617.

Volek JS, et al. The effects of creatine supplementation on muscular performance and body composition responses to short-term resistance training overreaching. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(5-6):628-637.

Waddington G, et al. Creatine supplementation for sprint and jumping performance in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(9):2514-2521.

Vitamin E Complex

Key Takeaways Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage, reducing the risk of chronic diseases. The vitamin E complex includes…

L-Glutamine and Gut Health: Benefits and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Glutamine is essential for gut health. Benefits include improved digestion and reduced inflammation. Potential side effects are rare but can occur in high…

Taurine: The Mighty Amino Acid for Optimal Health

Key Takeaways Taurine supports heart health, regulates blood pressure, and reduces oxidative stress. Essential for muscle function, brain health, and cognitive function. Aids in insulin…

L-Carnitine: Benefits, Dosage, and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Carnitine supports fat metabolism and energy production. Benefits include enhanced exercise performance and improved heart health. Proper dosing minimizes potential side effects. Understanding…

Trimethylglycine TMG: Betaine Anhydrous Explained

Key Takeaways Betaine Anhydrous (TMG) is a compound found naturally in various foods and offers several health benefits. TMG supports liver health by reducing fatty…

Spirulina: Health Benefits and Uses

Key Takeaways Spirulina boosts immune function with its high nutrient content and antioxidant properties. Rich in proteins and essential vitamins, enhances overall nutrition. Helps reduce…

Berberine Has 11 More Incredible Benefits Than You Thought

Berberine is a compound found in several plants that has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. It has recently gained popularity…

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways CLA is a type of fatty acid found primarily in animal products like beef and dairy. Known for potential benefits such as weight…

TUDCA Benefits for Health

Key Takeaways TUDCA promotes liver health, aiding cell protection and repair. Enhances digestion by improving bile flow and supporting gut health. May protect brain health…

Postbiotics: What They Are and Why They Are Important

Key Takeaways Postbiotics 101: They’re beneficial by-products from probiotics that consume prebiotics Boosts Immunity: Postbiotics sharpen your immune system, helping fight off pathogens and reducing…

Medium Chain Triglycerides (MCTs): Uncovering 5 Health Benefits

This potent, natural source of energy has gained considerable attention in recent years for its impressive array of benefits. MCT oil is a versatile addition…

Creatine Myths Debunked: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways Common myths about creatine, such as it causing kidney damage, weight gain, and being a steroid, are widespread but unsupported by scientific evidence….