Key Takeaways

- Gout results from the accumulation of uric acid crystals in the joints, causing severe pain and inflammation.

- High uric acid levels are often linked to metabolic issues and excessive fructose consumption.

- Fructose, not red meat, is a primary contributor to elevated uric acid and gout development.

- Proper management of gout involves reducing sugar intake and optimizing nutrient balance.

- Addressing underlying metabolic dysfunctions is essential for long-term gout relief.

Introduction

Gout is a form of arthritis characterized by sudden and severe pain, swelling, and redness in the joints, most often in the big toe.

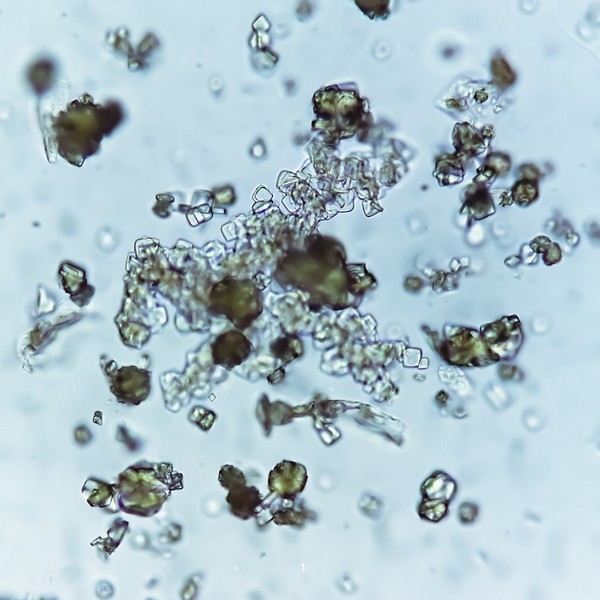

It occurs when uric acid crystals accumulate in the joints, causing inflammation and pain.

Gout is closely related to high levels of uric acid in the blood, but several factors influence its development, including diet, metabolic health, and lifestyle.

Causes and Risk Factors

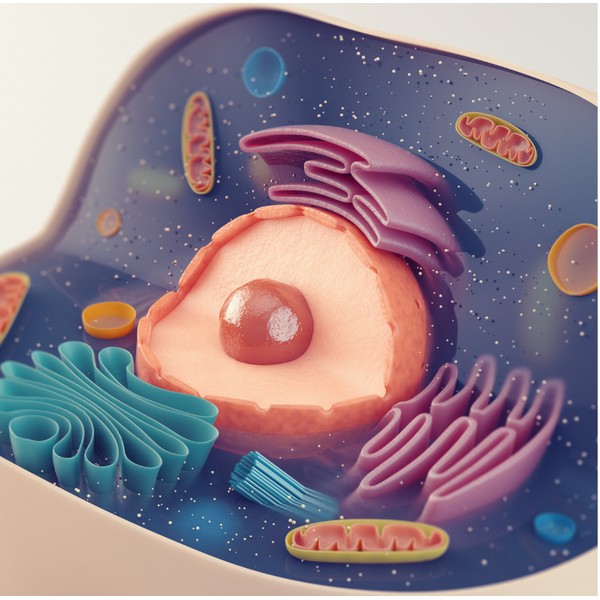

Uric Acid and Gout

Uric acid is a natural waste product formed when the body breaks down purines. Normally, uric acid is dissolved in the blood and eliminated through the kidneys.

However, when uric acid levels become too high, it can crystallize and settle in the joints, leading to gout.

The main drivers of elevated uric acid include metabolic issues, fructose consumption, and impaired kidney function.

The Role of Fructose in Gout

Fructose, found in sugary drinks and processed foods, is a major contributor to high uric acid levels.

Unlike glucose, fructose metabolism rapidly generates uric acid, particularly in the liver. Excessive fructose consumption has been linked to metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and gout.

Reducing fructose intake is key to preventing gout flares and managing uric acid levels.

Common Triggers for Gout Attacks

Gout attacks can be triggered by various factors, including:

- High consumption of fructose or sugar-laden foods

- Alcohol intake, especially beer

- Dehydration

- Sudden increases in physical activity or stress

- Certain medications that raise uric acid levels, like diuretics

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Common Symptoms

The most common symptom of gout is intense joint pain, often starting in the big toe, though other joints can be affected. Additional symptoms include:

- Swelling and redness in the affected joint

- Warmth and tenderness around the joint

- Limited joint movement due to pain

- Gout attacks, which can occur suddenly and last several days

Diagnosing Gout

Gout is typically diagnosed through physical examinations, blood tests to check uric acid levels, and imaging studies like ultrasounds or X-rays to detect uric acid crystals in the joints.

Joint fluid tests can also confirm the presence of uric acid crystals.

Treatment and Management

Dietary Adjustments

Managing gout involves making key dietary changes to reduce uric acid levels and prevent gout flares. Prioritizing nutrient-dense, low-sugar foods while reducing fructose intake is needed.

Contrary to popular belief, red meat is not a major cause of gout and provides essential nutrients like iron, zinc, and B vitamins.

Instead, eliminating sugary foods and drinks, especially those containing high-fructose corn syrup, is essential for reducing gout risk.

Medication Options

Medications are often prescribed to manage gout, especially during acute flare-ups. These include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Used to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Colchicine: Helps reduce inflammation during a gout attack.

- Allopurinol: Lowers uric acid levels by reducing its production in the body.

- Probenecid: Increases uric acid excretion through the kidneys.

While medications are effective, long-term management should focus on lifestyle changes that address the underlying causes of high uric acid.

Long-Term Management Strategies

In addition to dietary changes and medications, managing gout involves other lifestyle adjustments:

- Stay hydrated to support kidney function and uric acid excretion.

- Maintain a healthy weight to reduce the metabolic stress associated with high uric acid levels.

- Limit alcohol consumption, as it can interfere with uric acid excretion and trigger gout attacks.

Preventing Gout Flares

Reducing Fructose Intake

As fructose significantly contributes to elevated uric acid levels, cutting back on sugary drinks and processed foods is vital.

A diet rich in whole, low-carbohydrate foods supports metabolic health and prevents gout flares.

Optimizing Nutrient Intake

Eating a bioavailable nutrient-rich diet ensures the body gets essential nutrients like copper, which plays a key role in managing oxidative stress and iron regulation.

Proper nutrient balance helps the body manage uric acid more effectively.

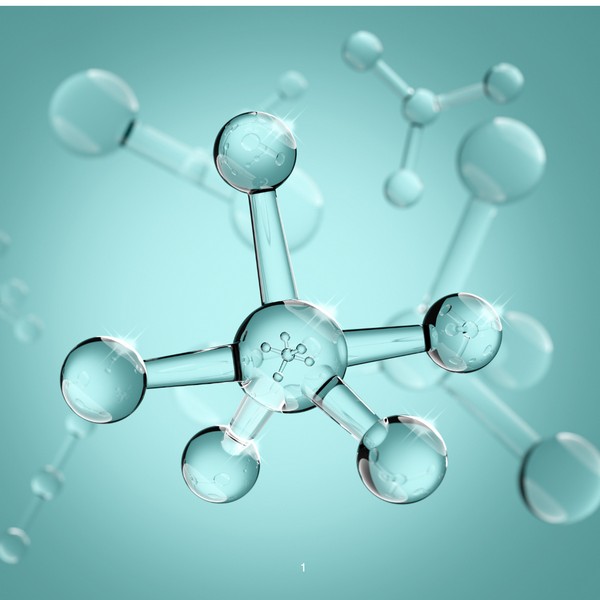

Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB)

Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) is one of the main ketone bodies produced by the liver during fat metabolism.

BHB is produced through a process called ketogenesis, where fats are broken down into ketones in the liver.

This occurs during times of carbohydrate restriction, fasting, or prolonged exercise. The body converts stored fat into ketones, with BHB being the primary ketone that circulates in the bloodstream and provides energy.

Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) has shown promising effects in reducing inflammation related to gout. Research indicates that BHB inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key driver in gout’s inflammatory response, particularly in neutrophils.

This inhibition reduces the production of IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in gouty flares.

The anti-inflammatory properties of BHB offer a potential therapeutic avenue for treating gout, providing relief from the intense joint pain and inflammation associated with the condition.

Exercise and Weight Management

Regular physical activity and maintaining a healthy weight help improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and lower the risk of metabolic conditions that contribute to gout.

However, sudden intense physical activity may trigger gout attacks, so exercise should be moderate and consistent.

Conclusion

Gout is a painful condition rooted in metabolic imbalances and high uric acid levels. While often misunderstood, the primary contributors to gout are fructose consumption and metabolic dysfunction, not red meat. Managing gout requires a combination of dietary changes, medication when needed, and long-term lifestyle adjustments that target the root causes of elevated uric acid. By focusing on reducing fructose intake and optimizing metabolic health, individuals can effectively manage and prevent gout flare-ups.

FAQs

What causes gout?

Gout is caused by the accumulation of uric acid crystals in the joints, often triggered by metabolic issues, fructose consumption, and impaired kidney function.

Is red meat a cause of gout?

No, red meat is not a primary cause of gout. The real culprit is excessive fructose consumption, which raises uric acid levels.

How can I prevent gout flare-ups?

Prevent gout flare-ups by reducing sugar and fructose intake, staying hydrated, maintaining a healthy weight, and following a nutrient-dense diet.

What is the role of fructose in gout?

Fructose is metabolized into uric acid, which contributes to gout development. Limiting sugary drinks and processed foods helps manage uric acid levels.

Can gout be cured?

While there is no cure for gout, it can be effectively managed through lifestyle changes, proper diet, and medications that reduce uric acid levels.

Research

Ayoub-Charette S, Liu Q, Khan TA, Au-Yeung F, Blanco Mejia S, de Souza RJ, Wolever TM, Leiter LA, Kendall C, Sievenpiper JL. Important food sources of fructose-containing sugars and incident gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2019 May 5;9(5):e024171. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024171. PMID: 31061018; PMCID: PMC6502023.

Bai, L., Zhou, J.-B., Zhou, T., Newson, R.B. and Cardoso, M.A., 2021. Incident gout and weight change patterns: a retrospective cohort study of US adults. Arthritis Research & Therapy, [online] 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-021-02461-7.

Basaranoglu, M., Basaranoglu, G., & Bugianesi, E. (2015). Carbohydrate intake and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Fructose as a weapon of mass destruction. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition, 4(2), 109-116. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.11.05

Cristina, M. (2023). Insulin and the kidneys: A contemporary view on the molecular basis. Frontiers in Nephrology, 3, 1133352.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fneph.2023.1133352

Ghio, A.J., Ford, E.S., Kennedy, T.P. and Hoidal, J.R., 2005. The association between serum ferritin and uric acid in humans. Free Radical Research, [online] 39(3), pp.337–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715760400026088.

Goldberg, E. L., Asher, J. L., Molony, R. D., Shaw, A. C., Zeiss, C. J., Wang, C., Morozova-Roche, L. A., Herzog, R. I., Iwasaki, A., & Dixit, V. D. (2017). β-hydroxybutyrate deactivates neutrophil NLRP3 inflammasome to relieve gout flares. Cell Reports, 18(9), 2077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.004

Jamnik, J., Rehman, S., Blanco Mejia, S., de Souza, R.J., Khan, T.A., Leiter, L.A., Wolever, T.M.S., Kendall, C.W.C., Jenkins, D.J.A. and Sievenpiper, J.L., 2016. Fructose intake and risk of gout and hyperuricemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open, [online] 6(10), p.e013191. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013191.

Lanaspa, M.A., Sanchez-Lozada, L.G., Cicerchi, C., Li, N., Roncal-Jimenez, C.A., Ishimoto, T., Le, M., Garcia, G.E., Thomas, J.B., Rivard, C.J., Andres-Hernando, A., Hunter, B., Schreiner, G., Rodriguez-Iturbe, B., Sautin, Y.Y. and Johnson, R.J., 2012. Uric Acid Stimulates Fructokinase and Accelerates Fructose Metabolism in the Development of Fatty Liver. PLoS ONE, [online] 7(10), p.e47948. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047948.

Lanaspa, M.A., Tapia, E., Soto, V., Sautin, Y. and Sánchez-Lozada, L.G., 2011. Uric Acid and Fructose: Potential Biological Mechanisms. Seminars in Nephrology, [online] 31(5), pp.426–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.08.006.

Maiuolo, J., Oppedisano, F., Gratteri, S., Muscoli, C. and Mollace, V., 2016. Regulation of uric acid metabolism and excretion. International Journal of Cardiology, [online] 213, pp.8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.109.

Mainous, A.G., Knoll, M.E., Everett, C.J., Matheson, E.M., Hulihan, M.M. and Grant, A.M., 2011. Uric Acid as a Potential Cue to Screen for Iron Overload. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, [online] 24(4), pp.415–421. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.110015.

Muscelli, E., 1996. Effect of insulin on renal sodium and uric acid handling in essential hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, [online] 9(8), pp.746–752.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-7061(96)00098-2.

Nakagawa, T., Lanaspa, M. A., & Johnson, R. J. (2019). The effects of fruit consumption in patients with hyperuricaemia or gout. Rheumatology, 58(7), 1133-1141. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez128

Pina, A.F., Borges, D.O., Meneses, M.J., Branco, P., Birne, R., Vilasi, A. and Macedo, M.P., 2020. Insulin: Trigger and Target of Renal Functions. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, [online] 8.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.00519.

Rasool, M., Malik, A., Jabbar, U., Begum, I., Qazi, M.H., Asif, M., Naseer, M.I., Ansari, S.A., Jarullah, J., Haque, A. and Jamal, M.S., 2016. Effect of iron overload on renal functions and oxidative stress in beta thalassemia patients. Saudi Medical Journal, [online] 37(11), pp.1239–1242. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2016.11.16242.

Rho, Y.H., Zhu, Y. and Choi, H.K., 2011. The Epidemiology of Uric Acid and Fructose. Seminars in Nephrology, [online] 31(5), pp.410–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.08.004.

Singh, J.A., Reddy, S.G. and Kundukulam, J., 2011. Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, [online] 23(2), pp.192–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0b013e3283438e13.

Skøtt, P., Hother-Nielsen, O., Bruun, N.E., Giese, J., Nielsen, M.D., Beck-Nielsen, H. and Parving, H.-H., 1989. Effects of insulin on kidney function and sodium excretion in healthy subjects. Diabetologia, [online] 32(9). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00274259.

Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Wu, J., Xie, D., Yang, T., Li, H. and Xiong, Y., 2020. Associations of serum iron and ferritin with hyperuricemia and serum uric acid. Clinical Rheumatology, [online] 39(12), pp.3777–3785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05164-7.

Yamanaka H. [Alcohol ingestion and hyperuricemia]. Nihon Rinsho. 1996 Dec;54(12):3369-73. Japanese. PMID: 8976122.

Oxidative Stress: Causes, Effects, Solutions

Key Takeaways Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in the body, leading to cellular damage. Chronic oxidative stress contributes to…

Ceruloplasmin: The Master Antioxidant

Key Takeaways: Ceruloplasmin is a copper-containing enzyme essential for iron metabolism and preventing oxidative stress. It helps transport iron safely, preventing iron overload in tissues…

Gout: Symptoms & Natural Treatment

Key Takeaways Gout results from the accumulation of uric acid crystals in the joints, causing severe pain and inflammation. High uric acid levels are often…

The Randle Cycle: Glucose Fat Energy Dilemma

Key Takeaways The Randle Cycle explains how the body chooses between burning glucose and fatty acids for energy. Enzymes and hormones play a key role…

Diatomaceous Earth: Natural Uses & Benefits

Key Takeaways – Diatomaceous earth is a natural powder made from fossilized algae called diatoms. – It helps cleanse the body of toxins and heavy…

Elimination Diets: Find the Foods Behind Your Symptoms

Key Takeaways Elimination diets identify food intolerances by removing and reintroducing specific foods. Divided into two phases: elimination and reintroduction. Items like gluten, soy, and…

Melatonin: Functions and Benefits

Key Takeaways Melatonin helps regulate sleep-wake cycles, signaling the body to rest as it gets dark. It acts as an antioxidant, protecting cells from damage….

The EWG Dirty Dozen: What You Need to Know

Key Takeaways The Dirty Dozen list highlights fruits and vegetables with the highest levels of pesticide residues. In 2024, strawberries, spinach, and kale top the…

Are Energy Drinks Dangerous?

Key Takeaways: Caffeine is the most common stimulant in energy drinks. Sugar, though harmful, is widely used in energy drinks. Electrolytes help maintain hydration and…

11 Amazing Tips to Improve Your Sleep Quality

Limit Power NapsModulate Sunlight ExposurePay Attention to CaffeineSchedule BedtimePlan Ahead for DinnertimeMelatonin: Not what you thoughtSleep EnvironmentHot Bath or ShowerEliminate Blue LightSleep StackAdrenal CocktailMagnesium The…

Adrenal Cocktail: Recipe and Benefits

Key Takeaways The adrenal cocktail supports adrenal health and maintains energy levels. Combines potassium, sodium, and vitamin C for effective adrenal nourishment. Consumed in the…

Osteoarthritis Symptoms & Home Remedies

Key Takeaways Lifestyle adjustments and alternative therapies contribute to overall symptom management. Low-impact exercises and physical activity help maintain mobility and reduce pain. Heat and…

Natural Remedies for Common Ailments: From Headaches to Allergies

Key Takeaways The appeal of natural remedies lies in their holistic approach, fewer side effects, and environmental sustainability. Specific natural remedies can effectively alleviate common…

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid)

Adrenal Fatigue: Symptoms & Prevention

Key Takeaways: Adrenal fatigue is often linked to prolonged stress, leading to tiredness, brain fog, and mood swings. Disruptions in cortisol production can affect energy,…

Superoxide Dismutase: Your Body’s Antioxidant Defender

Key Takeaways SOD protects against oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals. Copper is necessary for SOD to function. Low SOD activity can lead to aging,…

Does Grounding or Earthing Actually Work?

Autism: Causes, Symptoms, and Management

Key Takeaways Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition that varies widely in symptoms and severity. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to…

Bromate: Its Impact on Your Thyroid & Nervous System

Key Takeaways Bromate is a toxic byproduct from water disinfection, impacting thyroid and nervous system health. It interferes with iodine, leading to thyroid dysfunction and…

Gestational Diabetes Management: Expert Tips for Success

Key Highlights Gestational diabetes, marked by glucose intolerance during pregnancy, requires careful blood sugar control. A healthy pregnancy with gestational diabetes includes regular exercise, a…

DNA & Longevity: Can You Live to 200?

Key Takeaways: Longevity is shaped by a mix of genetics and lifestyle. Certain genes are linked to longer lifespans. Lifestyle choices can influence how long…

Managing Menopause Symptoms – A Guide to Navigate this Life Stage

Exercise RoutineManaging Stress Improving Sleep HabitsSeeking Emotional Support:Adjusting Your DietConsidering Alternative TherapiesFrequently Asked Questions Menopause is a natural stage in a woman’s life marking the…

Do Artificial Sweeteners Cause Weight Gain? The Surprising Truth

Key Takeaways – Artificial sweeteners may disrupt gut microbiome balance, impacting digestion and immune health. – These sweeteners can interfere with natural metabolism, leading to…

Sunburn Prevention: Holistic and Natural Approaches

Key Takeaways A poor diet increases the risk of sunburn and skin damage. Short, regular sun exposure reduces the risk of sunburn. Early morning and…

Why Sunlight is Essential for a Healthy Life

Key Takeaways Sunlight helps the body produce vitamin D, supporting bone health and immune function. Exposure to sunlight can improve mood and reduce symptoms of…

How Insulin Regulates Blood Sugar

Key Takeaways Insulin helps regulate blood sugar by moving glucose into cells. Imbalances in insulin levels can cause conditions like diabetes. Insulin resistance can lead…

Fluoride: Risks & Controversies

Key Takeaways Fluoride is widely used in dental products and water supplies, but its safety is debated. Overexposure to fluoride can lead to conditions like…

Do Artificial Sweeteners Cause Weight Gain? The Surprising Truth

Key Takeaways – Artificial sweeteners may disrupt gut microbiome balance, impacting digestion and immune health….

What You Need to Know About Salt and Your Health

Table of ContentsThe Health Benefits of Unrefined Sea SaltElectrolyte BalanceMineral ContentImproved HydrationBoosted Energy LevelsImmune SupportImproved…

How To Optimize Your Weight Loss Efforts

1. Get Your Beauty Sleep for Optimal Weight Loss2. Natural Solutions for Weight Loss3. Stress…

11 Amazing Tips to Improve Your Sleep Quality

Limit Power NapsModulate Sunlight ExposurePay Attention to CaffeineSchedule BedtimePlan Ahead for DinnertimeMelatonin: Not what you…

7 Simple Tips for Lowering Blood Pressure Naturally

Maintaining healthy blood pressure levels is essential for overall well-being, as high blood pressure can…

Proteolytic Enzymes and Heart Health: What the Research Shows

Your heart works tirelessly to pump blood throughout your body, delivering essential nutrients and oxygen…

Is Eating Sugar Really That Bad For Your Health?

Should You Really Be Concerned? In short, YES! Thank you, that’s all folks, and do…

Natural Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Effective Remedies Explored

Understanding IBSSymptoms of IBSRole of Diet in IBSNatural Remedies for IBSSupplements for IBSRole of Probiotics…

Medium Chain Triglycerides (MCTs): Uncovering 5 Health Benefits

This potent, natural source of energy has gained considerable attention in recent years for its…

7 Remedies for Kidney Stones: A Comprehensive Guide

Key Takeaways Staying well-hydrated and adopting a balanced diet can help prevent kidney stones. Knowing…

Berberine Has 11 More Incredible Benefits Than You Thought

Berberine is a compound found in several plants that has been used for centuries in…