Key Takeaways

- Rich in Nutrients: Sea moss is packed with essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, supporting overall health and wellness.

- Supports Immune Function: Its high vitamin C and zinc content help boost the immune system.

- Promotes Skin Health: Sea moss contains collagen-building nutrients that improve skin elasticity and hydration.

- Digestive Benefits: Sea moss is high in prebiotic fiber, supporting a healthy gut and regular digestion.

- Sustainability: Harvested sustainably, sea moss is an eco-friendly addition to diets.

Introduction

Sea moss, also known as Irish moss, is a type of red algae found along the rocky Atlantic coasts.

Known for its gelatinous texture and nutrient-rich profile, sea moss has been used for centuries in traditional medicine and as a food additive.

Its growing popularity in health circles is due to its extensive health benefits.

Nutritional Content of Sea Moss

Vitamins and Minerals

Sea moss is a powerhouse of nutrients, including high levels of iodine, potassium, and magnesium.

These minerals support various bodily functions, from thyroid health to muscle function.

Sea moss is also rich in vitamins A, C, E, and B-complex, contributing to immune support, skin health, and energy production.

Antioxidants and Bioactive Compounds

Sea moss contains unique compounds like carrageenan, which have anti-inflammatory properties.

Its antioxidants help neutralize free radicals, reducing oxidative stress and promoting overall health.

Health Benefits of Sea Moss

Immune Support

Sea moss’s high vitamin C and zinc content are important for supporting a healthy immune system.

These nutrients help strengthen the body’s defenses against infections and illnesses.

Skin and Hair Health

Sea moss contains nutrients that support collagen production, essential for maintaining skin elasticity and hydration.

Regular use can lead to healthier skin and stronger hair.

Digestive Health

Sea moss is a good source of prebiotic fiber, which feeds beneficial gut bacteria. This helps maintain a balanced gut microbiome and promotes regular digestion.

How to Use Sea Moss

Culinary Applications

Sea moss is versatile in the kitchen. It can be made into a gel and added to smoothies, soups, and desserts. Its neutral taste makes it easy to add to a variety of recipes.

Supplements and Dosage

Sea moss is available in various forms, including capsules, powders, and gels.

While it is generally safe to consume, it’s important to follow recommended dosages to avoid excessive intake of iodine and other nutrients.

Environmental Sustainability of Sea Moss

Harvesting Practices

Sea moss is harvested sustainably, making it an eco-friendly option. Its cultivation helps support coastal communities and provides a renewable resource for various industries.

FAQ

What are the main nutrients in sea moss?

Sea moss is rich in iodine, potassium, magnesium, and vitamins A, C, E, and B-complex.

How can I use sea moss in my diet?

Sea moss can be made into a gel and added to smoothies, soups, and desserts, or taken as a supplement.

Is sea moss good for skin health?

Yes, sea moss contains collagen-boosting nutrients that improve skin elasticity and hydration.

How does sea moss support immune function?

Sea moss is high in vitamin C and zinc, which are essential for a healthy immune system.

Is sea moss environmentally sustainable?

Yes, sea moss is harvested sustainably, supporting coastal ecosystems and communities.

Research

Ahn, B.R., Moon, H.E., Kim, H.R., Jung, H.A., & Choi, J.S. (2012). Neuroprotective effect of edible brown alga Eisenia bicyclis on amyloid beta peptide-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Archives of Pharmacal Research, 35(11), 1989–1998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-012-1116-5.

Al-Asmakh, M., Anuar, F., Zadjali, F., Rafter, J. and Pettersson, S., 2012. Gut microbial communities modulating brain development and function. Gut Microbes, [online] 3(4), pp.366–373.

https://doi.org/10.4161/gmic.21287.

Alghazwi, M., Kan, Y.Q., Zhang, W., Gai, W.P., Garson, M.J., & Smid, S. (2016). Neuroprotective activities of natural products from marine macroalgae during 1999–2015. Journal of Applied Phycology, 28(6), 3599–3616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-016-0908-2.

Bae, Y.J., Bu, S.Y., Kim, J.Y., Yeon, J.-Y., Sohn, E.-W., Jang, K.-H., Lee, J.-C., & Kim, M.-H. (2011). Magnesium supplementation through seaweed calcium extract rather than synthetic magnesium oxide improves femur bone mineral density and strength in ovariectomized rats. Biological Trace Element Research, 144(1–3), 992–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-011-9073-2.

Barbosa, M., Valentão, P. and Andrade, P., 2014. Bioactive Compounds from Macroalgae in the New Millennium: Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Marine Drugs, [online] 12(9), pp.4934–4972.

https://doi.org/10.3390/md12094934.

Bazan, N.G., Molina, M.F., & Gordon, W.C. (2011). Docosahexaenoic acid signalolipidomics in nutrition: Significance in aging, neuroinflammation, macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Annual Review of Nutrition, 31(1), 321–351. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104635.

Bath, S.C., Steer, C.D., Golding, J., Emmett, P., & Rayman, M.P. (2013). Effect of inadequate iodine status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). The Lancet, 382(9889), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60436-5.

Blanco Garcia, A., Dirks, R.P., Kals, J., Palstra, A.P., & Poelman, M. (2018). Immunomodulatory effects of dietary seaweeds in L.P.S. challenged Atlantic salmon Salmo salar as determined by deep R.N.A. sequencing of the head kidney transcriptome. Front Physiol, 9, 625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00625.

Bobomuratov, T., Isakova, G., Akramova, D., & Kuziev, A. (2011). Chronic nonspecific diseases of the lungs (CNDL) and iodine deficiency diseases in children. Eur Respir J, 38(Suppl 55), 1164. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/38/Suppl_55/p1164.

Cornish, M.L., Critchley, A.T., & Mouritsen, O.G. (2017). Consumption of seaweeds and the human brain. Journal of Applied Phycology, 29(5), 2377–2398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-016-1049-3.

Fleurence, J., & Levine, I.A. (Eds.). (2016). Seaweed in health and disease prevention. Academic Press.

Gómez-Zorita, S., González-Arceo, M., Trepiana, J., Eseberri, I., Fernández-Quintela, A., Milton-Laskibar, I., Aguirre, L., González, M., & Portillo, M.P. (2020). Anti-obesity effects of macroalgae. Nutrients, 12(8), 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082378.

Guo, F., Huang, C., Cui, Y., Momma, H., Niu, K., & Nagatomi, R. (2019). Dietary seaweed intake and depressive symptoms in Japanese adults: A prospective cohort study. Nutr J, 18(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-019-0486-7.

Ha, W.H., & Park, D.H. (2013). Effect of seaweed extract on hair growth promotion in experimental study of C57BL/6 mice. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2013.14.1.1.

Heffernan, N., Smyth, T.J., FitzGerald, R.J., Soler-Vila, A., & Brunton, N. (2014). Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of pressurised liquid and solid–liquid extracts from four Irish origin macroalgae. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 49(7), 1765–1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.12512.

Mahendran, S., Maheswari, P., Sasikala, V., Rubika, J.J., & Pandiarajan, J. (2021). In vitro antioxidant study of polyphenol from red seaweeds dichotomously branched Gracilaria edulis and robust sea moss Hypnea valentiae. Toxicology Reports, 8, 1404–1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.07.006.

Mohamed, S., Hashim, S. N., & Rahman, H. A. (2012). Seaweeds: A sustainable functional food for complementary and alternative therapy. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 23(2), 83-96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2011.09.001

Panahi, Y., Badeli, R., Karami, G.-R., Badeli, Z., & Sahebkar, A. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of 6-week Chlorella vulgaris supplementation in patients with major depressive disorder. Complement Ther Med, 23(4), 598–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2015.06.010.

Rudtanatip, T., Lynch, S.A., Wongprasert, K., & Culloty, S.C. (2018). Assessment of the effects of sulfated polysaccharides extracted from the red seaweed Irish moss Chondrus crispus on the immune-stimulant activity in mussels Mytilus spp. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 75, 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2018.02.014.

Skibola, C.F. (2004). The effect of Fucus vesiculosus, an edible brown seaweed, upon menstrual cycle length and hormonal status in three pre-menopausal women: A case report. BMC Complement Altern Med, 4, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-4-10.

Tamama, K. (2021). Potential benefits of dietary seaweeds as protection against COVID-19. Nutr Rev, 79(7), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa126.

Vaugelade, P., Hoebler, C., Bernard, F., Guillon, F., Lahaye, M., Duee, P.H., & Darcy-Vrillon, B. (2000). Non-starch polysaccharides extracted from seaweed can modulate intestinal absorption of glucose and insulin response in the pig. Reprod Nutr Dev, 40(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1051/rnd:2000118.

Zinc Supplements: Risks and Dangers

Key Takeaways Zinc supports immunity, wound healing, and cell growth. High zinc supplement doses can cause health problems. Always consult a healthcare provider before taking…

Eggs: A Comprehensive Guide

Key Highlights Eggs are a nutritional powerhouse, containing all the essential vitamins and minerals needed for overall health. Vital role in a balanced diet, providing…

Benefits of Nutritional Yeast

Key Takeaways Nutritional yeast is a rich source of vitamins and minerals. It supports immune function and promotes skin health. Its cheesy flavor makes it…

Is Eating Sugar Really That Bad For Your Health?

Should You Really Be Concerned? In short, YES! Thank you, that’s all folks, and do have a good evening. Seriously though, extensive research has established…

What You Need to Know About Salt and Your Health

Table of ContentsThe Health Benefits of Unrefined Sea SaltElectrolyte BalanceMineral ContentImproved HydrationBoosted Energy LevelsImmune SupportImproved DigestionBalanced pH LevelsReduced Water RetentionHeart Health SupportStronger Bones and TeethEnhanced…

11 Electrifying Health Benefits of Trace Minerals

What are Trace Minerals?The Major Roles of Trace MineralsSources of Trace MineralsDeficiencies in Trace MineralsThe Impact of Trace Minerals on Specific Health ConditionsFrequently Asked Questions…

Red Palm Oil: Unveiling The Potent Health Benefits

Struggling to find the right oil for your health and kitchen? Red palm oil is packed with nutrients that might just be what you need….

CoQ10: What Is It and Why Is It Important?

Key Takeaways CoQ10 (Coenzyme Q10) is an antioxidant produced by the body, essential for energy production in cells. Levels of CoQ10 naturally decrease with age…

Boron: Benefits of a Lesser-Known Mineral

Key Takeaways Boron is a trace mineral with significant health benefits. It supports brain function, bone health, and hormonal balance. Understanding boron’s role can improve…

The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Your Wellbeing

Every bite we take is a step toward either wellness or illness. In our fast-paced world, ultra-processed foods have become a staple, silently shaping our…

Vitamin E Complex

Key Takeaways Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage, reducing the risk of chronic diseases. The vitamin E complex includes…

Protein: You probably need more

Key Takeaways Protein is needed for building and repairing body tissues. It supports muscle growth, immune function, and hormone production. Bioavailable sources of protein include…

How Cod Liver Oil Can Transform Your Health and Wellness

Cod liver oil has been used for centuries as a natural remedy for various health conditions. Packed with essential nutrients and fatty acids, cod liver…

How Stabilized Rice Bran Supports Digestive & Heart Health

Key Takeaways – Stabilized rice bran is a nutrient-rich source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. – The stabilization process prevents rancidity, making it a long-lasting…

Iron Overload: Symptoms & Prevention Tips

Key Takeaways: Iron overload happens when the body absorbs excessive iron, which can damage organs. Common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, and skin changes. Early…

Calcium Supplements: What You Need to Know

Key Takeaways Calcium supplements have been linked to heart disease and kidney stones. Excess calcium from supplements can lead to imbalances and health issues. Natural…

Actual Superfoods: Real Foods You Should Be Eating

Key Takeaways Superfoods are nutrient-dense foods, offering essential vitamins, minerals, and fats. Prioritize high-quality sources for optimal nutrition. They support overall health, boost energy, and…

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways CLA is a type of fatty acid found primarily in animal products like beef and dairy. Known for potential benefits such as weight…

Silica: for Healthier Skin, Hair, and Nails

Key Takeaways: Silica supports strong and healthy skin, hair, and nails. It promotes bone health by boosting collagen production. Silica helps improve joint flexibility and…

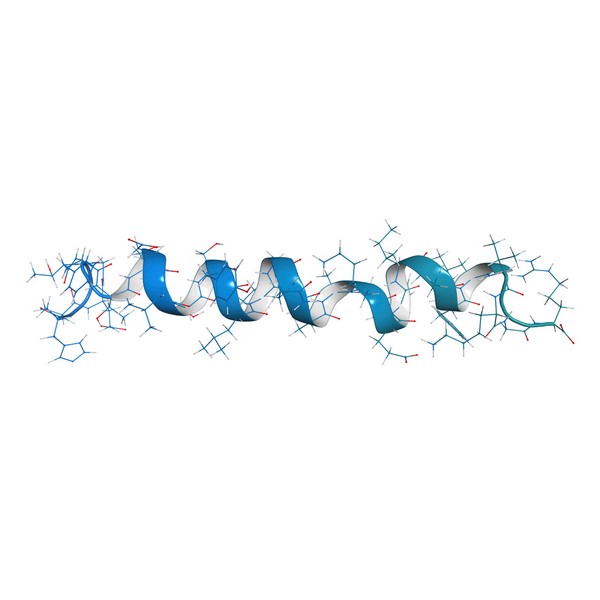

How Collagen Supports Healthy Skin, Joints, and More

Key Takeaways Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body, supporting the structure of skin, bones, and connective tissues. It helps maintain skin elasticity,…

6 Best Natural Ways to Manage Your Blood Sugar: A Quick & Easy Guide

1. Intermittent fasting2. Exercise3. Dietary fiber4. Sleep5. Weight loss6. SupplementationBioclinic NaturalsPGX BiotiquestSugar Shift Every time you eat it, it’s plotting something sinister. Sugar isn’t as…

Allulose: The Best Sugar Alternative

Key Takeaways Allulose is a low-calorie sweetener found naturally in some fruits. It does not raise blood sugar levels, making it suitable for diabetics. Allulose…

Cholesterol Misconceptions: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways: High inflammation and blood pressure are major risk factors for heart disease. Cholesterol is vital for hormone production, cell membrane structure, and digestion,…

Tallow: Benefits, Uses, and Nutrition

Key Takeaways: Tallow is a nutrient-rich animal fat with many practical uses. It contains valuable vitamins such as A, D, E, and K. Tallow is…

Healthy Fat: is Butter Better?

Key Takeaways Saturated fats, like those found in butter, may not be as harmful as once thought and can be part of a healthy diet….

Magnesium: Better Sleep, Stress Relief and More

Creatine Myths Debunked: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways Common myths about creatine, such as it causing kidney damage, weight gain, and being a steroid, are widespread but unsupported by scientific evidence….

TUDCA Benefits for Health

5 Major Benefits of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Key Takeaways Omega-3 fatty acids support heart health by reducing triglycerides and lowering blood pressure. They play an important role in brain function and development,…

13 Most Dangerous Foods Revealed

Key Highlights Fugu, or pufferfish, is one of the most poisonous foods in the world, with its organs containing a neurotoxin that can paralyze motor…

Liver: 5 Surprising Benefits Backed by Science

Hold on! Don’t run away! You need to read this. Liver is a highly nutritious organ meat that is often overlooked in modern diets. Packed…

L-Glutamine and Gut Health: Benefits and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Glutamine is essential for gut health. Benefits include improved digestion and reduced inflammation. Potential side effects are rare but can occur in high…

Spirulina: Health Benefits and Uses

Key Takeaways Spirulina boosts immune function with its high nutrient content and antioxidant properties. Rich in proteins and essential vitamins, enhances overall nutrition. Helps reduce…

Berberine Has 11 More Incredible Benefits Than You Thought

Berberine is a compound found in several plants that has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. It has recently gained popularity…

Taurine: The Mighty Amino Acid for Optimal Health

Key Takeaways Taurine supports heart health, regulates blood pressure, and reduces oxidative stress. Essential for muscle function, brain health, and cognitive function. Aids in insulin…

Postbiotics: What They Are and Why They Are Important

Key Takeaways Postbiotics 101: They’re beneficial by-products from probiotics that consume prebiotics Boosts Immunity: Postbiotics sharpen your immune system, helping fight off pathogens and reducing…

Do This! The Ultimate Guide to Fasting Safely and Effectively

In our increasingly busy lives, finding time to take care of our bodies can often take a backseat. One method that has gained attention recently…

ALA vs. DHA & EPA Omega-3: Why Source Matters

Key Takeaways ALA (Alpha-Linolenic Acid) is found in flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, but converts poorly to DHA and EPA. DHA and EPA are critical…

Natural Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Effective Remedies Explored

Understanding IBSSymptoms of IBSRole of Diet in IBSNatural Remedies for IBSSupplements for IBSRole of Probiotics in IBSFrequently Asked Questions Understanding IBS Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)…

Grains & Legumes Secretly Harming Your Health? Find Out Now!

Key Takeaways: – Grains and legumes contain antinutrients like lectins and phytic acid, which can interfere with nutrient absorption. – These foods may trigger digestive…

L-Carnitine: Benefits, Dosage, and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Carnitine supports fat metabolism and energy production. Benefits include enhanced exercise performance and improved heart health. Proper dosing minimizes potential side effects. Understanding…

8 Key Signs of Nutrient Deficiency

Key Takeaways Magnesium: A multitasker that aids in over 300 biochemical reactions in the body. Copper: Supports neurological function, cardiovascular and immune system health, iron…

Keto Diet 101: A Complete Beginner’s Guide

Key Highlights The ketogenic diet is a low-carb, high-fat diet that can lead to weight loss and has many health benefits. By reducing carbohydrate intake…

Carnivore Diet: Benefits, Risks, Food List & More

Key Takeaways The carnivore diet is a keto diet that only allows for animal-based foods, and has potential health benefits. Tips for success include hydrating,…

Copper: Little-Known Health Benefits

Key Takeaways Copper is an essential trace mineral with benefits, including ceruloplasmin production, energy production and antioxidant properties. Copper is critical for brain health by…

5-HTP: Natural Ways to Boost Serotonin and Improve Mood

Key Takeaways: 5-HTP is a natural compound that helps boost serotonin levels in the brain. It can support mood regulation, sleep improvement, and stress reduction….

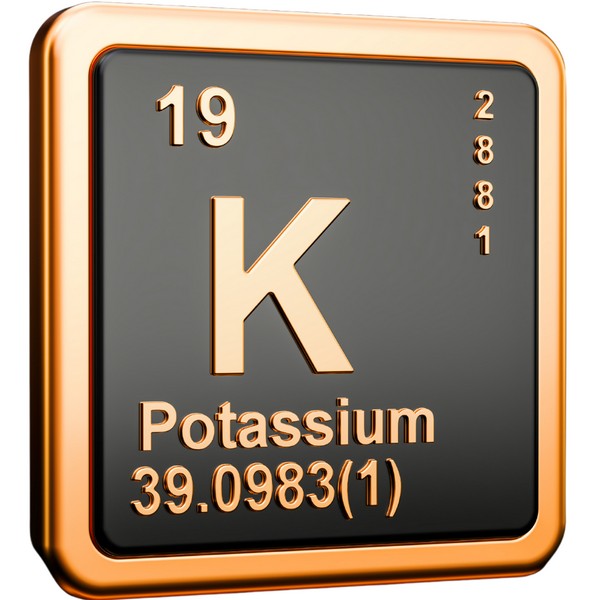

Potassium: Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways Potassium is essential for regulating fluid balance, nerve signals, and muscle function. It supports heart health and helps maintain proper blood pressure. Adequate…

Increase GLP-1 Agonists Naturally

Key Takeaways: GLP-1 agonists regulate appetite, insulin production, and blood sugar levels. Regular exercise and quality sleep maintain optimal GLP-1 levels. High-protein, low-carb diets effectively…

Bee Pollen: Nature’s Secret Superfood

Key Takeaways Bee pollen is packed with essential nutrients and offers numerous health benefits. It supports immune function, boosts energy, and promotes overall well-being. Adding…

Medium Chain Triglycerides (MCTs): Uncovering 5 Health Benefits

This potent, natural source of energy has gained considerable attention in recent years for its impressive array of benefits. MCT oil is a versatile addition…

Vitamin A (Retinol): Essential Nutrient for Health

Key Takeaways: Natural Vitamin A, also known as Retinol, is crucial for vision, immune function, and skin health. Retinol is essential for healthy vision, particularly…

Whole Food Vitamin C Complex: Expert Tips for Health

Key Highlights Whole food vitamin C complex is essential for a strong immune system and overall health. Unlike synthetic ascorbic acid, whole food vitamin C…

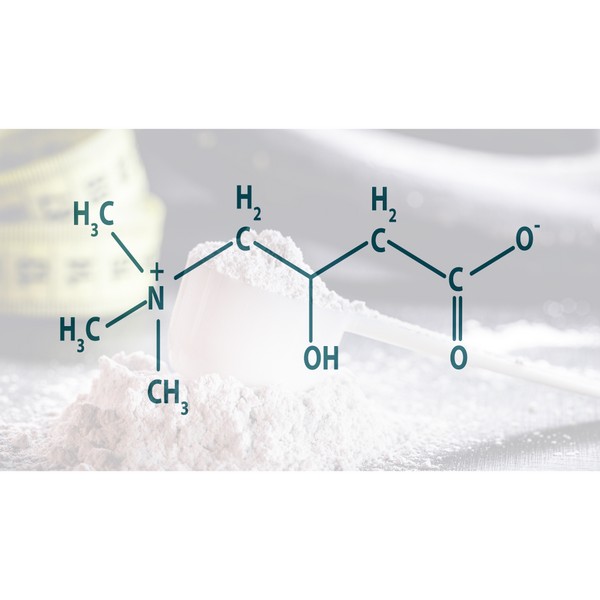

Trimethylglycine TMG: Betaine Anhydrous Explained

Key Takeaways Betaine Anhydrous (TMG) is a compound found naturally in various foods and offers several health benefits. TMG supports liver health by reducing fatty…