Key Takeaways

- The stress response includes four primary reactions, each serving as a survival mechanism.

- The fight response involves confronting the threat, often with aggression or assertiveness.

- The flight response triggers an urge to escape or avoid danger, prioritizing safety through withdrawal.

- The freeze response occurs when an individual becomes immobilized, unable to act or react in the face of stress.

- The fawn response is characterized by people-pleasing behaviors aimed at diffusing conflict and avoiding harm.

Introduction

Stress responses are our body’s way of reacting to perceived threats or challenges. These responses, often involuntary, are deeply rooted in our survival mechanisms.

The most common stress responses are Fight, Flight, Freeze, and Fawn. Understanding these can help in managing stress better and improving mental health.

| Response | Behavior |

|---|---|

| Fight | Aggression, confrontation |

| Flight | Avoidance, escaping |

| Freeze | Immobility, inaction |

| Fawn | People-pleasing, compliance |

The Fight Response

Definition and Characteristics

The Fight response is the body’s instinct to confront a threat aggressively. This reaction often comes with increased adrenaline, heightened alertness, and a readiness to take action.

Individuals experiencing this response may feel a surge of energy, become defensive, or engage in confrontational behavior.

Evolutionary Purpose

The Fight response evolved as a survival mechanism. When early humans encountered predators or other threats, the ability to stand ground and fight could mean the difference between life and death.

It was essential for protecting oneself, family, or territory.

Modern Implications

Today, the Fight response can manifest in less physically dangerous situations, such as arguments or workplace conflicts.

While it can be beneficial in asserting oneself, it can also lead to unnecessary aggression and stress.

Balancing this response is crucial for maintaining healthy relationships and reducing stress.

The Flight Response

Definition and Characteristics

The Flight response is characterized by the urge to escape from a threatening situation. This response often involves increased heart rate, quickened breathing, and a strong desire to flee from the source of stress.

People may avoid situations or withdraw from conflicts when in this mode.

Evolutionary Purpose

The Flight response helped early humans survive by avoiding danger. When faced with overwhelming threats, fleeing was often the safest option.

It enabled humans to escape predators or hostile environments, ensuring survival.

Modern Implications

In the modern world, the Flight response can manifest as avoiding conflicts, stressful tasks, or challenging situations.

While sometimes beneficial, chronic avoidance can lead to unresolved issues and increased anxiety.

Recognizing when to confront rather than flee is important for personal growth and stress management.

The Freeze Response

Definition and Characteristics

The Freeze response involves a temporary paralysis or inability to act in the face of stress. Individuals might feel stuck, numb, or unable to decide or take action.

This response is often accompanied by a sense of dissociation or detachment from the situation.

Evolutionary Purpose

Freezing was a survival strategy for early humans when neither fighting nor fleeing was possible.

By staying still and quiet, they could avoid detection by predators. It was a last resort when other options seemed too risky.

Modern Implications

Today, the Freeze response can occur during overwhelming stress, such as during a traumatic event or when faced with a high-pressure decision.

While it can protect in some situations, chronic freezing can hinder decision-making and lead to feelings of helplessness.

Learning to move past this response is key to dealing with stress effectively.

The Fawn Response

Definition and Characteristics

The Fawn response is the tendency to appease or placate others to avoid conflict.

This reaction often involves people-pleasing behavior, excessive compliance, and putting others’ needs before one’s own. Individuals may go out of their way to avoid upsetting others.

Evolutionary Purpose

The Fawn response likely evolved as a social survival mechanism. By maintaining harmony and avoiding aggression within a group, early humans could ensure their acceptance and protection within the community.

It was a way to navigate social hierarchies and avoid being ostracized.

Modern Implications

In contemporary settings, the Fawn response can lead to unhealthy relationships and a lack of personal boundaries.

While being agreeable can be beneficial, overdoing it can result in neglecting one’s own needs and desires.

Understanding when to assert oneself rather than always appease is important for maintaining self-esteem and mental health.

Factors Influencing Stress Responses

| Response | Description | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Fight | Confront stress | Restlessness, increased heart rate |

| Flight | Escape from stress | Urge to run, panic |

| Freeze | Immobility in stress | Dissociation, detachment |

| Fawn | Appease to avoid stress | Placating behavior, compliance |

Personal Factors

Each person’s dominant stress response can be influenced by personality traits, past experiences, and individual resilience.

People may default to one response based on their life history or learned behaviors.

Environmental Factors

The environment plays a significant role in triggering different stress responses. Situations such as workplace dynamics, family stress, or societal pressures can activate specific responses depending on perceived threats or stressors.

Psychological and Biological Influences

Psychological and biological factors, such as brain chemistry and hormonal balances, also shape how individuals respond to stress.

Understanding these influences can help in managing stress responses more effectively.

Coping Strategies and Management

Breathe, don’t vent: Turning down the heat is key to managing anger https://t.co/EnsyVRtJgj pic.twitter.com/Jt0xkLRanJ

— AIHCP (@AIHCP) March 18, 2024

Identifying Your Dominant Response

Recognizing which stress response you default to is the first step in managing stress. Self-awareness can be developed through reflection, journaling, or therapy.

Strategies for Each Response

For Fight: Practice calming techniques, such as deep breathing, to reduce aggression.

For Flight: Gradually face fears to build confidence and reduce avoidance behavior.

For Freeze: Engage in grounding exercises to break the paralysis and encourage action.

For Fawn: Set boundaries and practice assertiveness to prioritize personal needs.

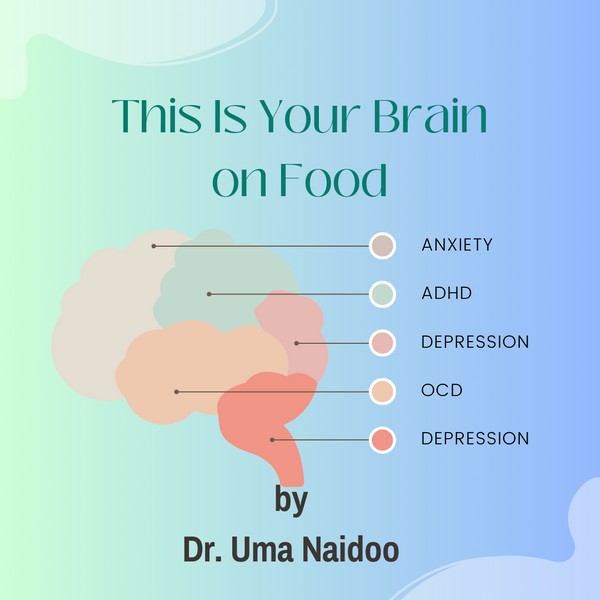

The Impact of Nutrition

The brain is a physical organ that requires nutrients to work properly. In addition to foundational healthy fat and protein, micronutrients are vital.

Copper

Copper is essential for proper brain function and neurotransmitter synthesis, which are directly linked to mood regulation and stress response.

A deficiency in copper can lead to disruptions in these neurotransmitters, potentially increasing the likelihood of anxiety and depression.

This may heighten the Fight or Flight response, as the brain becomes more sensitive to perceived threats, leading to increased irritability or anxiety.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that supports the growth, survival, and differentiation of neurons, and it’s vital for cognitive function, learning, and memory.

Copper acts as a cofactor for enzymes that are involved in the synthesis and regulation of BDNF. Adequate levels of copper help ensure that BDNF can effectively promote neural health and plasticity.

Conversely, copper deficiency may impair BDNF activity, potentially leading to cognitive issues and a weakened ability to manage stress.

Copper is involved in the enzyme activity that contributes to the synthesis of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles.

Melatonin is important for sleep quality, which directly impacts stress responses. Adequate copper levels support proper melatonin production, helping to maintain regular sleep patterns. This, in turn, can reduce the intensity of stress responses like Fight, Flight, Freeze, or Fawn.

A deficiency in copper might disrupt melatonin production, leading to sleep disturbances, which can exacerbate stress and make managing these responses more challenging.

Magnesium

Magnesium plays a key role in the regulation of the nervous system and is often referred to as the “relaxation mineral.”

It helps control the release of stress hormones like cortisol and supports healthy sleep patterns.

A deficiency in magnesium can result in heightened stress, anxiety, and nervous system hyperactivity.

This can amplify the Fight and Freeze responses, making individuals more prone to aggression or paralysis in stressful situations.

It can also impair the ability to calm down after a stress response has been triggered.

B Vitamins Deficiencies

Vitamin B1 (Thiamine)

Thiamine is crucial for energy metabolism and the proper functioning of the nervous system.

A deficiency can lead to fatigue, irritability, and a decreased ability to cope with stress, potentially intensifying the Fight or Flight response due to impaired energy production and brain function.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine)

Vitamin B6 is involved in neurotransmitter synthesis, including serotonin and dopamine, which regulate mood and stress response.

A deficiency in B6 can lead to mood disturbances, increased anxiety, and depression, potentially making the Freeze or Fawn responses more likely as the brain struggles to process stress effectively.

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is essential for maintaining healthy nerve cells and producing DNA and RNA. A deficiency in B12 can cause neurological and psychological issues, including mood swings, anxiety, and cognitive impairments.

This deficiency may influence all four stress responses, potentially exacerbating them due to the brain’s reduced ability to cope with stress.

How Deficiencies Factor into Stress Responses

- Exacerbation of Fight Response: Deficiencies in these nutrients can lead to increased irritability, anxiety, and a heightened sense of threat, making individuals more prone to react aggressively or defensively in stressful situations.

- Amplification of Flight Response: Anxiety and nervous system dysregulation caused by these deficiencies can make individuals more likely to avoid or flee from stressful situations, as their ability to cope is compromised.

- Intensification of Freeze Response: Nutrient deficiencies can cause fatigue, brain fog, and an impaired stress response, leading to an increased likelihood of freezing or becoming paralyzed by stress due to a lack of proper neurological function.

- Increase in Fawn Response: Deficiencies, particularly in B vitamins, can cause mood disturbances and low self-esteem, potentially making individuals more likely to engage in people-pleasing behaviors to avoid conflict or stress.

Seeking professional help when these responses become maladaptive or overwhelming is important for long-term well-being.

Conclusion

Understanding the Fight, Flight, Freeze, and Fawn responses allows for better stress management and healthier interactions. By recognizing these reactions in oneself, individuals can develop coping strategies that promote resilience and emotional balance.

FAQs

What triggers each stress response?

Triggers can vary widely, from external threats like conflicts to internal pressures like anxiety or trauma.

Can stress responses change over time?

Yes, responses can evolve based on life experiences, therapy, and self-awareness.

Is one stress response better than the others?

No single response is inherently better; each can be adaptive or maladaptive depending on the situation.

How can I manage a maladaptive stress response?

Therapy, self-awareness, and specific coping strategies tailored to the response can help manage maladaptive behaviors.

What role does therapy play in addressing stress responses?

Therapy can help identify triggers, teach coping strategies, and provide tools to manage stress responses effectively.

Research

Aigner, C., 2022. Love or fear? The please/appease survival response: interrupting the cycle of trauma.

Arendt, J., 2019. Melatonin: countering chaotic time cues. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, p.391.

Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, Ayers D. Physiology, Stress Reaction. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2023. PMID: 31082164.

https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk541120

Dean, C., 2017. The magnesium miracle. Ballantine books.

Driskell, J., 2022. Pathways to Anxiety. All About Anxiety: An Introductory Guide to Neuroscience, Assessment, and Intervention.

Faryadi, Q., 2012. The magnificent effect of magnesium to human health: a critical review. International Journal of Applied, 2(3), pp.118-126.

Gaier, E. D., Eipper, B. A., & Mains, R. E. (2013). Copper signaling in the mammalian nervous system: Synaptic effects. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 91(1), 2-19.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23143

Gancitano, G. and Reiter, R.J., 2022. The Multiple Functions of Melatonin: Applications in the Military Setting. Biomedicines, 11(1), p.5.

Kubossek, S., 2024. “I Am Weary with Holding it In”: Fight, Flight and Freeze in Jeremiah’s Final Confession. Canadian Journal of Theology, Mental Health and Disability, 4(1), pp.19-31.

Malter, R., 2008. Magnesium Deficiency and the Mind/Body Connection. Education and Health Resources.

Owca, J., 2020. The association between a psychotherapist’s theoretical orientation and perception of complex trauma and repressed anger in the fawn response (Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology).

Paredes, R., 2022. Understanding Trauma: The 6 Types of Trauma Responses. Understanding Trauma: The 6 Types of Trauma Responses.

Rosanoff, A. The 2-to-1 Calcium-to-Magnesium Ratio.

Rosanoff, A. The Important Role of Nutritional Magnesium and Calcium Balance in Humans Living with Stress.

Schlote, S., 2017. Somatic Experiencing® and Attachment Principles.

Seelig, M., 2003. The Magnesium Factor: How One Simple Nutrient Can Prevent, Treat, and Reverse High Blood Pressure, Heart Disease, Diabetes, and Other Chronic Conditions. Penguin.

Selye, H., 2002. Physiology of stress. Jacqueline Mark-Geraci, Julie Champagne Bolduc, Advanced Clinical Insights. 5th Ed. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishing, pp.35-48.

Shah, A., Offering Counselling, Workshops & Training In Pretoria Since 2010.

Watts, D.L., 1990. Trace elements and neuropsychological problems as reflected in tissue mineral analysis (TMA) patterns. Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine, 5(3), pp.159-166.

Whyte, K.F., 1989. Adrenergic Control of Potassium and Magnesium: Interaction with Drug Therapy. University of Glasgow (United Kingdom).

Winhall, J. Addiction from the Bottom Up: A Felt Sense Polyvagal Model of Addiction | Somatic Psychotherapy Today.

Zingela, Z., Stroud, L., Cronje, J., Fink, M. and van Wyk, S., 2022. The psychological and subjective experience of catatonia: a qualitative study. BMC Psychology, 10(1), p.173.

Trimethylglycine TMG: Betaine Anhydrous Explained

Calcium Supplements: What You Need to Know

Key Takeaways Calcium supplements have been linked to heart disease and kidney stones. Excess calcium from supplements can lead to imbalances and health issues. Natural…

11 Electrifying Health Benefits of Trace Minerals

What are Trace Minerals?The Major Roles of Trace MineralsSources of Trace MineralsDeficiencies in Trace MineralsThe Impact of Trace Minerals on Specific Health ConditionsFrequently Asked Questions…

Natural Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Effective Remedies Explored

Understanding IBSSymptoms of IBSRole of Diet in IBSNatural Remedies for IBSSupplements for IBSRole of Probiotics in IBSFrequently Asked Questions Understanding IBS Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)…

Benefits of Nutritional Yeast

Key Takeaways Nutritional yeast is a rich source of vitamins and minerals. It supports immune function and promotes skin health. Its cheesy flavor makes it…

Do This! The Ultimate Guide to Fasting Safely and Effectively

In our increasingly busy lives, finding time to take care of our bodies can often take a backseat. One method that has gained attention recently…

Spirulina: Health Benefits and Uses

Key Takeaways Spirulina boosts immune function with its high nutrient content and antioxidant properties. Rich in proteins and essential vitamins, enhances overall nutrition. Helps reduce…

How Cod Liver Oil Can Transform Your Health and Wellness

Cod liver oil has been used for centuries as a natural remedy for various health conditions. Packed with essential nutrients and fatty acids, cod liver…

Magnesium: Better Sleep, Stress Relief and More

Postbiotics: What They Are and Why They Are Important

Key Takeaways Postbiotics 101: They’re beneficial by-products from probiotics that consume prebiotics Boosts Immunity: Postbiotics sharpen your immune system, helping fight off pathogens and reducing…

Tallow: Benefits, Uses, and Nutrition

Key Takeaways: Tallow is a nutrient-rich animal fat with many practical uses. It contains valuable vitamins such as A, D, E, and K. Tallow is…

Carnivore Diet: Benefits, Risks, Food List & More

Key Takeaways The carnivore diet is a keto diet that only allows for animal-based foods, and has potential health benefits. Tips for success include hydrating,…

6 Best Natural Ways to Manage Your Blood Sugar: A Quick & Easy Guide

1. Intermittent fasting2. Exercise3. Dietary fiber4. Sleep5. Weight loss6. SupplementationBioclinic NaturalsPGX BiotiquestSugar Shift Every time you eat it, it’s plotting something sinister. Sugar isn’t as…

The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Your Wellbeing

Every bite we take is a step toward either wellness or illness. In our fast-paced world, ultra-processed foods have become a staple, silently shaping our…

ALA vs. DHA & EPA Omega-3: Why Source Matters

Key Takeaways ALA (Alpha-Linolenic Acid) is found in flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, but converts poorly to DHA and EPA. DHA and EPA are critical…

Cholesterol Misconceptions: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways: High inflammation and blood pressure are major risk factors for heart disease. Cholesterol is vital for hormone production, cell membrane structure, and digestion,…

How Stabilized Rice Bran Supports Digestive & Heart Health

Key Takeaways – Stabilized rice bran is a nutrient-rich source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. – The stabilization process prevents rancidity, making it a long-lasting…

Increase GLP-1 Agonists Naturally

Key Takeaways: GLP-1 agonists regulate appetite, insulin production, and blood sugar levels. Regular exercise and quality sleep maintain optimal GLP-1 levels. High-protein, low-carb diets effectively…

Silica: for Healthier Skin, Hair, and Nails

CoQ10: What Is It and Why Is It Important?

Key Takeaways CoQ10 (Coenzyme Q10) is an antioxidant produced by the body, essential for energy production in cells. Levels of CoQ10 naturally decrease with age…

Whole Food Vitamin C Complex: Expert Tips for Health

Key Highlights Whole food vitamin C complex is essential for a strong immune system and overall health. Unlike synthetic ascorbic acid, whole food vitamin C…

Creatine Myths Debunked: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways Common myths about creatine, such as it causing kidney damage, weight gain, and being a steroid, are widespread but unsupported by scientific evidence….

5-HTP: Natural Ways to Boost Serotonin and Improve Mood

Key Takeaways: 5-HTP is a natural compound that helps boost serotonin levels in the brain. It can support mood regulation, sleep improvement, and stress reduction….

Potassium: Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways Potassium is essential for regulating fluid balance, nerve signals, and muscle function. It supports heart health and helps maintain proper blood pressure. Adequate…

Berberine Has 11 More Incredible Benefits Than You Thought

Berberine is a compound found in several plants that has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. It has recently gained popularity…

Is Eating Sugar Really That Bad For Your Health?

Should You Really Be Concerned? In short, YES! Thank you, that’s all folks, and do have a good evening. Seriously though, extensive research has established…

8 Key Signs of Nutrient Deficiency

Key Takeaways Magnesium: A multitasker that aids in over 300 biochemical reactions in the body. Copper: Supports neurological function, cardiovascular and immune system health, iron…

Liver: 5 Surprising Benefits Backed by Science

Hold on! Don’t run away! You need to read this. Liver is a highly nutritious organ meat that is often overlooked in modern diets. Packed…

5 Major Benefits of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Key Takeaways Omega-3 fatty acids support heart health by reducing triglycerides and lowering blood pressure. They play an important role in brain function and development,…

Benefits of Sea Moss Explained

Key Takeaways Rich in Nutrients: Sea moss is packed with essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, supporting overall health and wellness. Supports Immune Function: Its high…

L-Carnitine: Benefits, Dosage, and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Carnitine supports fat metabolism and energy production. Benefits include enhanced exercise performance and improved heart health. Proper dosing minimizes potential side effects. Understanding…

TUDCA Benefits for Health

Key Takeaways TUDCA promotes liver health, aiding cell protection and repair. Enhances digestion by improving bile flow and supporting gut health. May protect brain health…

13 Most Dangerous Foods Revealed

Key Highlights Fugu, or pufferfish, is one of the most poisonous foods in the world, with its organs containing a neurotoxin that can paralyze motor…

Taurine: The Mighty Amino Acid for Optimal Health

Key Takeaways Taurine supports heart health, regulates blood pressure, and reduces oxidative stress. Essential for muscle function, brain health, and cognitive function. Aids in insulin…

Healthy Fat: is Butter Better?

Key Takeaways Saturated fats, like those found in butter, may not be as harmful as once thought and can be part of a healthy diet….

Actual Superfoods: Real Foods You Should Be Eating

Key Takeaways Superfoods are nutrient-dense foods, offering essential vitamins, minerals, and fats. Prioritize high-quality sources for optimal nutrition. They support overall health, boost energy, and…

Medium Chain Triglycerides (MCTs): Uncovering 5 Health Benefits

This potent, natural source of energy has gained considerable attention in recent years for its impressive array of benefits. MCT oil is a versatile addition…

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways CLA is a type of fatty acid found primarily in animal products like beef and dairy. Known for potential benefits such as weight…

Boron: Benefits of a Lesser-Known Mineral

Key Takeaways Boron is a trace mineral with significant health benefits. It supports brain function, bone health, and hormonal balance. Understanding boron’s role can improve…

Red Palm Oil: Unveiling The Potent Health Benefits

Struggling to find the right oil for your health and kitchen? Red palm oil is packed with nutrients that might just be what you need….

L-Glutamine and Gut Health: Benefits and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Glutamine is essential for gut health. Benefits include improved digestion and reduced inflammation. Potential side effects are rare but can occur in high…

Grains & Legumes Secretly Harming Your Health? Find Out Now!

Key Takeaways: – Grains and legumes contain antinutrients like lectins and phytic acid, which can interfere with nutrient absorption. – These foods may trigger digestive…

Copper: Little-Known Health Benefits

Key Takeaways Copper is an essential trace mineral with benefits, including ceruloplasmin production, energy production and antioxidant properties. Copper is critical for brain health by…

Zinc Supplements: Risks and Dangers

Key Takeaways Zinc supports immunity, wound healing, and cell growth. High zinc supplement doses can cause health problems. Always consult a healthcare provider before taking…

Bee Pollen: Nature’s Secret Superfood

Key Takeaways Bee pollen is packed with essential nutrients and offers numerous health benefits. It supports immune function, boosts energy, and promotes overall well-being. Adding…

Allulose: The Best Sugar Alternative

Key Takeaways Allulose is a low-calorie sweetener found naturally in some fruits. It does not raise blood sugar levels, making it suitable for diabetics. Allulose…

Eggs: A Comprehensive Guide

Key Highlights Eggs are a nutritional powerhouse, containing all the essential vitamins and minerals needed for overall health. Vital role in a balanced diet, providing…

Keto Diet 101: A Complete Beginner’s Guide

Key Highlights The ketogenic diet is a low-carb, high-fat diet that can lead to weight loss and has many health benefits. By reducing carbohydrate intake…

Vitamin A (Retinol): Essential Nutrient for Health

Key Takeaways: Natural Vitamin A, also known as Retinol, is crucial for vision, immune function, and skin health. Retinol is essential for healthy vision, particularly…

Protein: You probably need more

Key Takeaways Protein is needed for building and repairing body tissues. It supports muscle growth, immune function, and hormone production. Bioavailable sources of protein include…

Iron Overload: Symptoms & Prevention Tips

Key Takeaways: Iron overload happens when the body absorbs excessive iron, which can damage organs. Common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, and skin changes. Early…

Vitamin E Complex

Key Takeaways Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage, reducing the risk of chronic diseases. The vitamin E complex includes…

What You Need to Know About Salt and Your Health

Table of ContentsThe Health Benefits of Unrefined Sea SaltElectrolyte BalanceMineral ContentImproved HydrationBoosted Energy LevelsImmune SupportImproved DigestionBalanced pH LevelsReduced Water RetentionHeart Health SupportStronger Bones and TeethEnhanced…

How Collagen Supports Healthy Skin, Joints, and More

Key Takeaways Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body, supporting the structure of skin, bones, and connective tissues. It helps maintain skin elasticity,…