Key Takeaways

- Zinc supports immunity, wound healing, and cell growth.

- High zinc supplement doses can cause health problems.

- Always consult a healthcare provider before taking zinc supplements.

- Animal-based foods are the best sources of zinc.

- Zinc deficiency is rare with a meat-based diet.

Introduction

Zinc is an important mineral that plays various roles in maintaining health. A balanced diet provides all the zinc your body needs, along with other nutrients that work together harmoniously.

What is Zinc?

Zinc is a trace mineral that supports many vital functions in the body, including immune response, skin repair, and hormone production.

The body only needs zinc in small amounts, and these can be easily met through a diet that includes a variety of zinc-rich foods.

Health Benefits of Zinc

Immune Support

Zinc helps strengthen the immune system, enabling the body to fight off infections more effectively.

Obtaining zinc through natural food sources ensures your immune system gets the support it needs without the risks that come with excessive supplementation.

Skin Health

Zinc is beneficial for maintaining healthy skin, promoting wound healing, and reducing acne. Foods high in zinc, like meats and seeds, naturally contribute to better skin health without the potential side effects of supplements.

Hormonal Balance

Zinc is important for hormone regulation, particularly testosterone, and helps maintain overall hormonal health.

Getting zinc from food ensures that hormonal balance is achieved safely, without disrupting other essential minerals like copper.

Cognitive Function

Zinc is involved in brain health, influencing memory and learning. It supports cognitive function effectively, avoiding the dangers of high-dose supplements.

Reproductive Health

Zinc is essential for reproductive health and fertility in both men and women. Natural food sources of zinc provide a safe and effective way to support reproductive functions without the complications that can arise from supplement use.

Zinc-Rich Foods

Animal-Based Sources

- Red meat (beef, lamb)

- Shellfish (oysters, crab, lobster)

- Poultry (chicken, turkey)

- Dairy products (cheese, milk)

Plant-Based Sources

- Seeds (pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds)

- Nuts (cashews, almonds)

- Legumes (chickpeas, lentils)

- Whole grains (quinoa, oatmeal)

Dangers of Zinc Supplements

Interference with Copper

Metallothioneins are proteins in your body that help manage the levels of metals like zinc and copper. These proteins can store zinc and release it when needed. They also help protect your cells from damage by metals.

When you have too much zinc, metallothioneins get busy storing it. But here’s the problem: these proteins also grab onto copper, trapping it inside your cells and making it unavailable for your body to use.

If you keep taking in too much zinc, it can cause a copper deficiency because your body isn’t getting the copper it needs. This deficiency can lead to problems like anemia (low red blood cell count), weakness, and even issues with your nerves.

Copper is important for cardiovascular health, brain function, and the immune system. Zinc levels are best maintained through a well-rounded diet rather than supplements.

Potential Side Effects

Excessive zinc intake from supplements can cause nausea, stomach upset, and, over time, more serious health problems such as immune dysfunction and lowered HDL cholesterol.

High levels of zinc can also suppress immune function rather than enhance it, which defeats the purpose of taking zinc supplements in the first place.

Conclusion

Zinc is beneficial for many aspects of health, but the safest way to meet your zinc needs is through a balanced diet rich in zinc-containing foods. Avoiding zinc supplements helps prevent the risk of disrupting copper levels and other potential health issues, ensuring that your body functions optimally.

FAQs

Why should I avoid zinc supplements?

Zinc supplements can interfere with copper absorption, leading to a deficiency in this essential mineral. The risks associated with supplementation often outweigh the potential benefits, especially when zinc can be easily obtained from food.

What are the best food sources of zinc?

Excellent sources of zinc include red meat, shellfish, seeds, and nuts. A varied diet that includes these foods will help you meet your zinc needs naturally.

How does zinc affect copper levels?

Zinc and copper compete for absorption in the body. High levels of zinc from supplements can reduce copper absorption, leading to a deficiency that can cause serious health issues.

What are the first signs of zinc deficiency?

Poor immune response, hair loss, and slow healing are early indicators.

Research

Aggett, P.J., 2013. Copper. Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, [online] pp.397–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-375083-9.00062-3.

Botash, A.S., 1992. Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency in an Infant. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, [online] 146(6), p.709. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180069019.

Collins, J.F., 2020. Copper. Present Knowledge in Nutrition, [online] pp.409–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-66162-1.00024-x.

Duncan, A., Gallacher, G., & Willox, L., 2015. The role of the clinical biochemist in detection of zinc-induced copper deficiency. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563215595429.

Duncan, A., Morrison, I. and Bryson, S., 2023. Iatrogenic copper deficiency: Risks and cautions with zinc prescribing. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, [online] 89(9), pp.2825–2829. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15749.

Duncan, A., Talwar, D. and Morrison, I., 2015. The predictive value of low plasma copper and high plasma zinc in detecting zinc-induced copper deficiency. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry: International Journal of Laboratory Medicine, [online] 53(5), pp.575–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563215620821.

Duncan, A., Yacoubian, C., Watson, N. and Morrison, I., 2015. The risk of copper deficiency in patients prescribed zinc supplements. Journal of Clinical Pathology, [online] 68(9), pp.723–725. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202837.

Francis, Z., Book, G., Litvin, C. and Kalivas, B., 2022. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency: An Important Link. The American Journal of Medicine, [online] 135(8), pp.e290–e291.

https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(22)00244-3/fulltext.

Gupta, N. and Carmichael, M.F., 2023. Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency as a Rare Cause of Neurological Deficit and Anemia. Cureus. [online] https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43856.

Hambidge, M., 2000. Human Zinc Deficiency. The Journal of Nutrition, [online] 130(5), pp.1344S-1349S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/130.5.1344s.

Hassan, H.A., Netchvolodoff, C. and Raufman, J.-P., 2000. Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency in A Coin Swallower. American Journal of Gastroenterology, [online] 95(10), pp.2975–2977. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02336.x.

Hoffman HN 2nd, Phyliky RL, Fleming CR. Zinc-induced copper deficiency. Gastroenterology. 1988 Feb;94(2):508-12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90445-3. PMID: 3335323.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/0016-5085(88)90445-3/pdf

Igic, P.G., Lee, E., Harper, W. and Roach, K.W., 2002. Toxic Effects Associated With Consumption of Zinc. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, [online] 77(7), pp.713–716.

https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(11)62239-8/fulltext.

Maret, W., 2008. Metallothionein redox biology in the cytoprotective and cytotoxic functions of zinc. Experimental Gerontology, [online] 43(5), pp.363–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2007.11.005.

Myint, Z.W., Oo, T.H., Thein, K.Z., Tun, A.M. and Saeed, H., 2018. Copper deficiency anemia: review article. Annals of Hematology, [online] 97(9), pp.1527–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3407-5.

Naeim, F., Nagesh Rao, P., Song, S.X. and Grody, W.W., 2013. Disorders of Red Blood Cells—Anemias. Atlas of Hematopathology, [online] pp.675–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-385183-3.00061-9.

Osredkar, J., 2011. Copper and Zinc, Biological Role and Significance of Copper/Zinc Imbalance. Journal of Clinical Toxicology, [online] s3(01). https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0495.s3-001.

Pfeiffer, R.F., 2014. Neurologic manifestations of malabsorption syndromes. Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part II, [online] pp.621–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-4087-0.00042-5.

Pfeiffer, R.F., 2014. Other Neurologic Disorders Associated with Gastrointestinal Disease. Aminoff’s Neurology and General Medicine, [online] pp.237–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-407710-2.00013-8.

Powell, S.R., 2000. The Antioxidant Properties of Zinc. The Journal of Nutrition, [online] 130(5), pp.1447S-1454S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/130.5.1447s.

Prasad, A.S., 2008. Zinc in Human Health: Effect of Zinc on Immune Cells. Molecular Medicine, [online] 14(5–6), pp.353–357. https://doi.org/10.2119/2008-00033.prasad.

Thachil, J., Owusu-Ofori, S. and Bates, I., 2014. Haematological Diseases in the Tropics. Manson’s Tropical Infectious Diseases, [online] pp.894-932.e7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-5101-2.00066-2.

Wahab, A., Mushtaq, K., Borak, S. G., & Bellam, N., 2020. Zinc-induced copper deficiency, sideroblastic anemia, and neutropenia: A perplexing facet of zinc excess. Clinical Case Reports, 8(9), 1666-1671. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.2987.

Willis, M.S., Monaghan, S.A., Miller, M.L., McKenna, R.W., Perkins, W.D., Levinson, B.S., Bhushan, V. and Kroft, S.H., 2005. Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, [online] 123(1), pp.125–131. https://doi.org/10.1309/v6gvyw2qtyd5c5pj.

13 Most Dangerous Foods Revealed

Key Highlights Fugu, or pufferfish, is one of the most poisonous foods in the world, with its organs containing a neurotoxin that can paralyze motor…

Vitamin A (Retinol): Essential Nutrient for Health

Key Takeaways: Natural Vitamin A, also known as Retinol, is crucial for vision, immune function, and skin health. Retinol is essential for healthy vision, particularly…

Magnesium: Better Sleep, Stress Relief and More

Benefits of Sea Moss Explained

Key Takeaways Rich in Nutrients: Sea moss is packed with essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, supporting overall health and wellness. Supports Immune Function: Its high…

How Collagen Supports Healthy Skin, Joints, and More

Is Eating Sugar Really That Bad For Your Health?

Should You Really Be Concerned? In short, YES! Thank you, that’s all folks, and do have a good evening. Seriously though, extensive research has established…

Berberine Has 11 More Incredible Benefits Than You Thought

Berberine is a compound found in several plants that has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. It has recently gained popularity…

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways CLA is a type of fatty acid found primarily in animal products like beef and dairy. Known for potential benefits such as weight…

ALA vs. DHA & EPA Omega-3: Why Source Matters

Key Takeaways ALA (Alpha-Linolenic Acid) is found in flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, but converts poorly to DHA and EPA. DHA and EPA are critical…

Tallow: Benefits, Uses, and Nutrition

Key Takeaways: Tallow is a nutrient-rich animal fat with many practical uses. It contains valuable vitamins such as A, D, E, and K. Tallow is…

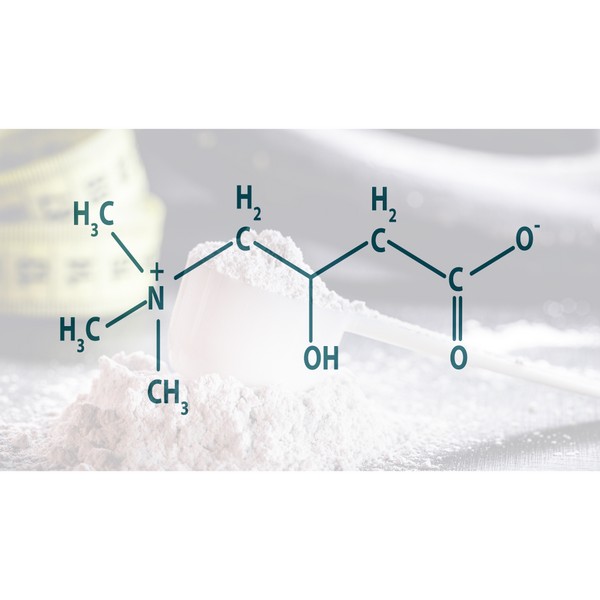

Trimethylglycine TMG: Betaine Anhydrous Explained

Iron Overload: Symptoms & Prevention Tips

Key Takeaways: Iron overload happens when the body absorbs excessive iron, which can damage organs. Common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, and skin changes. Early…

Silica: for Healthier Skin, Hair, and Nails

Key Takeaways: Silica supports strong and healthy skin, hair, and nails. It promotes bone health by boosting collagen production. Silica helps improve joint flexibility and…

Grains & Legumes Secretly Harming Your Health? Find Out Now!

Key Takeaways: – Grains and legumes contain antinutrients like lectins and phytic acid, which can interfere with nutrient absorption. – These foods may trigger digestive…

Postbiotics: What They Are and Why They Are Important

Key Takeaways Postbiotics 101: They’re beneficial by-products from probiotics that consume prebiotics Boosts Immunity: Postbiotics sharpen your immune system, helping fight off pathogens and reducing…

The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Your Wellbeing

Every bite we take is a step toward either wellness or illness. In our fast-paced world, ultra-processed foods have become a staple, silently shaping our…

Do This! The Ultimate Guide to Fasting Safely and Effectively

In our increasingly busy lives, finding time to take care of our bodies can often take a backseat. One method that has gained attention recently…

Increase GLP-1 Agonists Naturally

5 Major Benefits of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Key Takeaways Omega-3 fatty acids support heart health by reducing triglycerides and lowering blood pressure. They play an important role in brain function and development,…

Creatine Myths Debunked: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways Common myths about creatine, such as it causing kidney damage, weight gain, and being a steroid, are widespread but unsupported by scientific evidence….

Boron: Benefits of a Lesser-Known Mineral

Key Takeaways Boron is a trace mineral with significant health benefits. It supports brain function, bone health, and hormonal balance. Understanding boron’s role can improve…

How Stabilized Rice Bran Supports Digestive & Heart Health

Key Takeaways – Stabilized rice bran is a nutrient-rich source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. – The stabilization process prevents rancidity, making it a long-lasting…

Healthy Fat: is Butter Better?

Key Takeaways Saturated fats, like those found in butter, may not be as harmful as once thought and can be part of a healthy diet….

What You Need to Know About Salt and Your Health

Table of ContentsThe Health Benefits of Unrefined Sea SaltElectrolyte BalanceMineral ContentImproved HydrationBoosted Energy LevelsImmune SupportImproved DigestionBalanced pH LevelsReduced Water RetentionHeart Health SupportStronger Bones and TeethEnhanced…

Liver: 5 Surprising Benefits Backed by Science

Hold on! Don’t run away! You need to read this. Liver is a highly nutritious organ meat that is often overlooked in modern diets. Packed…

TUDCA Benefits for Health

Key Takeaways TUDCA promotes liver health, aiding cell protection and repair. Enhances digestion by improving bile flow and supporting gut health. May protect brain health…

Cholesterol Misconceptions: Separating Fact from Fiction

Key Takeaways: High inflammation and blood pressure are major risk factors for heart disease. Cholesterol is vital for hormone production, cell membrane structure, and digestion,…

How Cod Liver Oil Can Transform Your Health and Wellness

Cod liver oil has been used for centuries as a natural remedy for various health conditions. Packed with essential nutrients and fatty acids, cod liver…

Vitamin E Complex

Key Takeaways Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage, reducing the risk of chronic diseases. The vitamin E complex includes…

Carnivore Diet: Benefits, Risks, Food List & More

Key Takeaways The carnivore diet is a keto diet that only allows for animal-based foods, and has potential health benefits. Tips for success include hydrating,…

8 Key Signs of Nutrient Deficiency

Key Takeaways Magnesium: A multitasker that aids in over 300 biochemical reactions in the body. Copper: Supports neurological function, cardiovascular and immune system health, iron…

Calcium Supplements: What You Need to Know

Key Takeaways Calcium supplements have been linked to heart disease and kidney stones. Excess calcium from supplements can lead to imbalances and health issues. Natural…

Red Palm Oil: Unveiling The Potent Health Benefits

Struggling to find the right oil for your health and kitchen? Red palm oil is packed with nutrients that might just be what you need….

Protein: You probably need more

Key Takeaways Protein is needed for building and repairing body tissues. It supports muscle growth, immune function, and hormone production. Bioavailable sources of protein include…

Copper: Little-Known Health Benefits

Key Takeaways Copper is an essential trace mineral with benefits, including ceruloplasmin production, energy production and antioxidant properties. Copper is critical for brain health by…

CoQ10: What Is It and Why Is It Important?

Key Takeaways CoQ10 (Coenzyme Q10) is an antioxidant produced by the body, essential for energy production in cells. Levels of CoQ10 naturally decrease with age…

11 Electrifying Health Benefits of Trace Minerals

What are Trace Minerals?The Major Roles of Trace MineralsSources of Trace MineralsDeficiencies in Trace MineralsThe Impact of Trace Minerals on Specific Health ConditionsFrequently Asked Questions…

6 Best Natural Ways to Manage Your Blood Sugar: A Quick & Easy Guide

1. Intermittent fasting2. Exercise3. Dietary fiber4. Sleep5. Weight loss6. SupplementationBioclinic NaturalsPGX BiotiquestSugar Shift Every time you eat it, it’s plotting something sinister. Sugar isn’t as…

Taurine: The Mighty Amino Acid for Optimal Health

Key Takeaways Taurine supports heart health, regulates blood pressure, and reduces oxidative stress. Essential for muscle function, brain health, and cognitive function. Aids in insulin…

Whole Food Vitamin C Complex: Expert Tips for Health

Key Highlights Whole food vitamin C complex is essential for a strong immune system and overall health. Unlike synthetic ascorbic acid, whole food vitamin C…

Natural Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Effective Remedies Explored

Understanding IBSSymptoms of IBSRole of Diet in IBSNatural Remedies for IBSSupplements for IBSRole of Probiotics in IBSFrequently Asked Questions Understanding IBS Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)…

L-Glutamine and Gut Health: Benefits and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Glutamine is essential for gut health. Benefits include improved digestion and reduced inflammation. Potential side effects are rare but can occur in high…

Potassium: Benefits & Sources

Key Takeaways Potassium is essential for regulating fluid balance, nerve signals, and muscle function. It supports heart health and helps maintain proper blood pressure. Adequate…

Actual Superfoods: Real Foods You Should Be Eating

Key Takeaways Superfoods are nutrient-dense foods, offering essential vitamins, minerals, and fats. Prioritize high-quality sources for optimal nutrition. They support overall health, boost energy, and…

Zinc Supplements: Risks and Dangers

Key Takeaways Zinc supports immunity, wound healing, and cell growth. High zinc supplement doses can cause health problems. Always consult a healthcare provider before taking…

Medium Chain Triglycerides (MCTs): Uncovering 5 Health Benefits

This potent, natural source of energy has gained considerable attention in recent years for its impressive array of benefits. MCT oil is a versatile addition…

Bee Pollen: Nature’s Secret Superfood

Key Takeaways Bee pollen is packed with essential nutrients and offers numerous health benefits. It supports immune function, boosts energy, and promotes overall well-being. Adding…

L-Carnitine: Benefits, Dosage, and Side Effects

Key Takeaways L-Carnitine supports fat metabolism and energy production. Benefits include enhanced exercise performance and improved heart health. Proper dosing minimizes potential side effects. Understanding…

Keto Diet 101: A Complete Beginner’s Guide

Key Highlights The ketogenic diet is a low-carb, high-fat diet that can lead to weight loss and has many health benefits. By reducing carbohydrate intake…

5-HTP: Natural Ways to Boost Serotonin and Improve Mood

Key Takeaways: 5-HTP is a natural compound that helps boost serotonin levels in the brain. It can support mood regulation, sleep improvement, and stress reduction….

Allulose: The Best Sugar Alternative

Key Takeaways Allulose is a low-calorie sweetener found naturally in some fruits. It does not raise blood sugar levels, making it suitable for diabetics. Allulose…

Spirulina: Health Benefits and Uses

Key Takeaways Spirulina boosts immune function with its high nutrient content and antioxidant properties. Rich in proteins and essential vitamins, enhances overall nutrition. Helps reduce…

Eggs: A Comprehensive Guide

Key Highlights Eggs are a nutritional powerhouse, containing all the essential vitamins and minerals needed for overall health. Vital role in a balanced diet, providing…

Benefits of Nutritional Yeast

Key Takeaways Nutritional yeast is a rich source of vitamins and minerals. It supports immune function and promotes skin health. Its cheesy flavor makes it…